CHICAGO

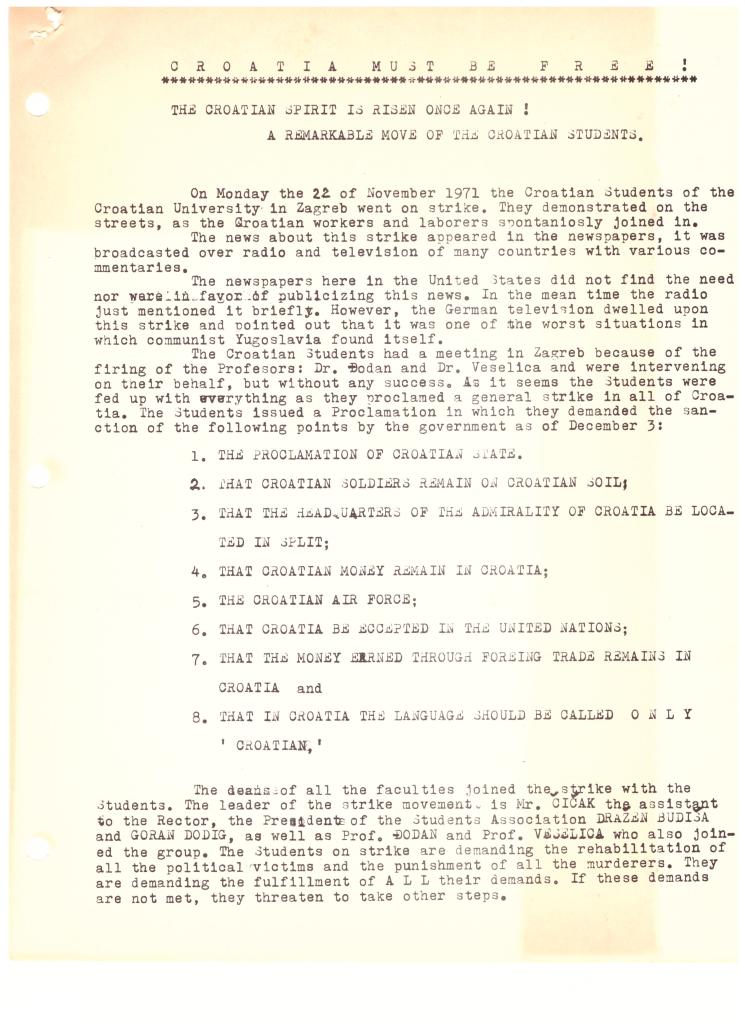

NEW YORK CITY

DETROIT

CLEVELAND

CHICAGO

NEW YORK CITY

DETROIT

CLEVELAND

Objavljeno: 05. veljače 2026, Portal Hrvatskoga kulturnog vijeća https://www.hkv.hr/hkvpedija/iseljenistvo/47001-a-cuvalo-crtica-iz-povijesti-hrvata-u-americi.html

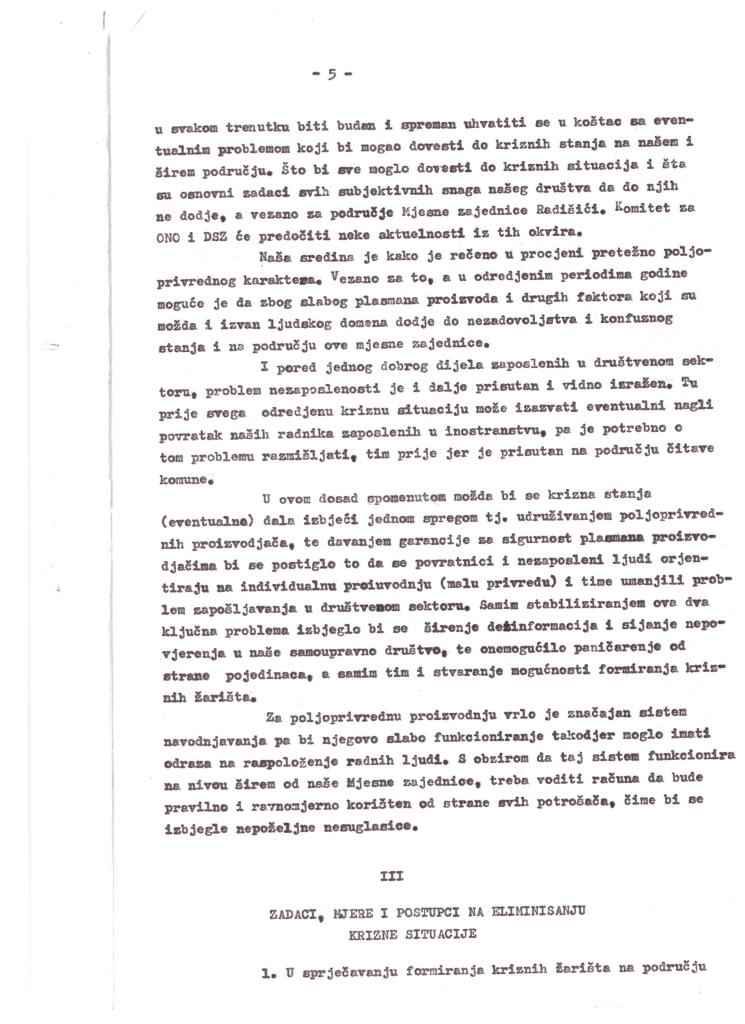

Prve godine prošloga stoljeća u Hrvatskoj su bile krvave i dramatične, moglo bi se reći i sudbonosne, a Hrvatima u Americi bile su, u najmanju ruku, zbunjujuće. Napomenimo, kraj Khuenova terora došao je u lipnju 1903. Približno u isto vrijeme krenulo se s politikom „novoga kursa”, koja je dvije godine poslije toga izrodila dvije važne rezolucije (Riječku i Zadarsku) i hrvatsko-srpsku koaliciju.

Bilo je to dramatično doba i u susjedstvu. U Bosni i Hercegovini godine 1903. smrt je okončala vladavinu Benjamina Kallaya, koji je pokušao nametnuti unitarizam i ideologiju „bosanske narodnosti”. Iste su godine (1903.) urotnici velikosrbi u Beogradu na divljački način pogubili kralja Aleksandra Obrenovića i kraljicu, na prijestolje doveli dinastiju Karađorđevića i zacrtali doskorašnje srpske osvajačke pohode. Tu su bili i početci Crne ruke (Ujedinjenje ili smrt), vojne tajne organizacije koja je organizirala „četnike” za terorističke pothvate u susjedstvu. Velikosrpski je cilj bio (i ostao) ujedinjenje „srpskih zemalja”.

Američki Hrvati toga vremena pomno su pratili domovinska događanja i pomagali na sve moguće načine svojemu narodu, ali su bili istodobno politički poprilično zatečeni. Pitanje je bilo: kojim putom u budućnost? Koju domovinsku politiku slijediti?

Kod nekih, hrvatsko-srpska suradnja u domovini bila je bezazleno pozdravljena. Drugi, premda nisu bili protiv „novoga kursa”, bili su oprezni. Treći su ostali nepokolebljivi i zagovarali ne samo očuvanje hrvatske državnosti nego i njezinu potpunu samostalnost. Četvrti, posebice neki koji su nekoć bili u austro-ugarskoj vojsci, ostali su vjerni caru Franji. Peti su bili sljedbenici socijalizma, radničkoga internacionalizma i jugoslavenstva, ali su ipak gotovo uvijek čuvali kakvo-takvo hrvatstvo u svojem identitetu.

Na primjer, tadašnje hrvatsko glasilo Naša sloga u San Franciscu zagovaralo je zajedničku hrvatsko-srpsku školu za doseljeničku djecu. Navodno, bio bi manji trošak za jedne i druge. Za takav projekt opravdanje im je davala koalicija u domovini. No drugi su ih ovako opominjali: „Mi se još uviek nalazimo u prilikama medjusobne nesigurnosti. Imade medju nama na jednoj i drugoj strani još uvijek ljudi, koji sa strahom gledaju, ako im brat ulazi u kuću, da mu ju i ne preotme, a zoveš li ga u nju, boji se, da se u njoj ne izgubi.” (Hrvatska Zastava, 4. svibnja 1905.)

San Francisco u stara vremena

Na takav oprez upozoravalo ih je i pisanje srpskih glasila u Americi. Na primjer, dok se u domovini krojila hrvatsko-srpska koalicija i pisalo o zbližavanju s „braćom Srbima”, srpsko glasilo Srbin u Pittsburghu među srpske zemlje ubrajalo je Dalmaciju i Bosnu i Hercegovinu. Naime, u to vrijeme vlasnikom i urednikom Srbina postao je Rade A. Porubović, od kojega su američki Hrvati očekivali normalnije i prijateljskije pisanje od prijašnjega uredništva. Ali kako tjednik Hrvatska zastava 18. svibnja 1905. piše, on je u svojem prvom uvodniku „pozdravio ostale srpske novine s obećanjem, da želi razvijati s njima složan rad za napredak Srpstva. Ipak moramo na žalost konstatirati, da Srbin ni sada pod novim vlasničtvom ne pokazuje volje stati na ono sviestnije šire narodno gledište sa kojega bi se obazirati imao na ostalo Slavenstvo, a tu na prvom mjestu na čistu narodnu si braću Hrvate. O njima novi urednik ni rieči ne spominje, naprotiv kao i do sada trpa pod rubriku ‘Srpstvo’ našu Dalmaciju te priepornu Bosnu i Hercegovinu.”

Komentator, po uobičajenom hrvatskom načinu, umjesto osude, na kraju ponizno uredniku Srbina kaže: „Bilo bez zamiere!” Ti hrvatsko-američki simpatizeri „novoga kursa” bili su za suradnju sa Srbima, ponajprije sa Srbima u Hrvatskoj, ali da to bude „bratski” i „pošteno”! Tada, kao i poslije, ponizno su opominjali „braću”: nemojte pretjeravati, hajdemo pošteno! Ali bilo je i ostalo uzalud „ćoravu namigivati”!

Srećom, među sljedbenicima ove jake struje bio je i velik broj domoljuba i sposobnih kulturnih radnika. Oni su otpočeli mnogo prije „novoga kursa” i potom nastavili organizirati narodne zajednice, dramska društva, župe, zborove, čitaonice, Sokolski savez i druge organizacije koje su čuvale identitet, kulturnu baštinu i jezik Hrvata u Americi. Gajili su i čuvali svoje, a njihovo pro-(jugo)slavenstvo je ipak bilo prolazno.

Treća snaga među američkim Hrvatima bili su i ostali oni koji nisu skretali s hrvatskoga povijesnoga hoda. Vjerovali su da hrvatski narod ima pravo na svoju slobodu i državnu samobitnost. Te su se snage uglavnom okupljale oko hrvatskih rimo- i grkokatoličkih župa, oko uglednijih svećenika i javnih radnika.

Nadalje, među američkim Hrvatima u početku 20. stoljeća bio je jedan broj i tzv. austriaka. Imali su i svoje organizacije. Uglavnom su dolazili iz Dalmacije jer je taj dio Hrvatske (1815. – 1918.) bio pod izravnom upravom Beča, a ne pod jurisdikcijom Hrvatskoga sabora i bana. Među njima bilo je i mnogo bivših carskih vojnika pa su ostali vjerni caru Franji! Bili su ponosni na Beč, a ne na Zagreb. S „austriacima” je bilo podosta prepucavanja i muke dok nisu polako postali potpuno svjesni svojega hrvatstva.

Kad je buknuo Prvi svjetski rat, posebice kad je Amerika ušla u rat, ostatci „austriaka” i hrvatski domoljubi bili su označeni kao (potencijalni) državni neprijatelji. U prvom redu bili su to oni koji su se protivili srljanju u zagrljaj Beogradu. To je bilo dovoljno da Amerikanci posumnjaju u njihovu lojalnost i mnoge Hrvate (i druge tzv. enemy aliens) zadrže pod nadzorom i represijom, a neki su završili i u logorima. Raspad Austro-Ugarske Monarhije bio je kraj i naših posljednjih „austriaka”.

Tadašnja posebna sekta među Hrvatima u Americi bili su socijalisti. Sa Slovencima i Srbima tvorili su Jugoslavensku socijalističku federaciju. Od te tri skupine, Hrvati su bili s najvećom internacionalističkom usmjerenošću i najtvrđi revolucionari. Dok su drugi, na primjer, dali podršku američkom ulasku u Prvi svjetski rat, naši socijalisti, odnosno komunisti, ostali su anti-ratnici i šutjeli do kraja rata. Njima su Amerika i kapitalizam bili krivi za sve nedaće i zla u svijetu. Bili su vrlo uporni i naporni, unosili su puno nemira u hrvatske zajednice diljem Amerike, posebice u većim gradovima.

Tada i poslije, našim tzv. socijalistima ta je „bolest” ostala trajna! Oni su ponosni internacionalisti! Uvijek vrište protiv Amerike i Zapada, a spremno imitiraju radikalne ideje sa Zapada i fanatično ih slijede, ne misleći na potrebe svojega naroda i države! Istina, u ime „viših” ideala i socijalne jednakosti, oni danas sebi i svojima osiguravaju „svjetliju budućnost” na račun države koju nisu ni htjeli!

Gledajući s današnje vremenske točke, među Hrvatima u Americi ishlapjelo je „austrijanstvo”, autonomaštvo, socijalizam i jugoslavizam…, ostalo je domoljubno hrvatstvo. Ali u slobodnoj državi Hrvatskoj sve jače se osjećaju neo-jugoslavizam, šuplji socijalizam i sa Zapada uvezene nove destruktivne ideologije, kojima se domaći aktivisti služe i na njima bez stida pokušavaju izvući korist.

Nažalost, odnedavno se u Americi zapaža klica neo-jugoslavizma na „znanstvenoj razini”. Naime, u tamošnjim slavističkim krugovima rodila se, s crvenom zvijezdom na čelu, udruga The New Yugoslav Studies Association. Kako može biti nova kad stara nije ni postojala! Tu je i ime osobe iz okrilja HAZU-a. Je li to klica bolesti za ponovno raslojavanje Hrvata u Americi? O tome bi trebalo voditi računa i u Zagrebu, ne samo u Americi.

Chicago nekoć

Dr. Ante Tresić-Pavičić, hrvatski političar i književnik, posjetio je 1905. Hrvate u Americi. Na skupu u San Franciscu, na kojem je Tresić govorio, pojavila se i skupinica „austriaka” koja je nazočne provocirala.

O tom događaju jedan izvjestitelj, među ostalim, donosi i „srčano” sročenu kletvu:

„Ti kukavni stvorovi, sramote 20. vijeka, za koje se ne može pravo odrediti pripadaju li kolu ludjaka ili bezumne marve, ti stvorovi čija je prošlost crna ko crna lopiža, ti stvorovi bez odgoja i karaktera, ti izdajnici svog roda, u životinjskoj svojoj bjesnoći, uzurlikaše se pred častnim našim zastupnikom i proslavljenim pjesnikom, rigajući spomenute povike. I ti hulitelji naše svetinje, našeg Hrvatstva, rodjeni kao i mi, na divnim žalima divnog našeg Jadrana, i oni su nekad tepali, učeći se govoriti sladke hrvatske riječi. I hrvatskom riječju zbore kroz cio svoj život i tom istom hrvatskom blagom riječju pogrdjuju predrago nam Hrvatstvo! Oj nesretni stvorovi, oj izmeti ljudstva, sakrijte se pred licima poštenih ljudi, bježi gamadi od onih koje u oči pogledati nesmiješ! Vi kukavice, vi odrodi, vi budale, stid vas bilo, ako za stid znate; sramite se svog gnjusnog zločina, koga na svom narodu počiniste! Vaša imena, koja bolje da neobstoje, zabilježiti će se u knjige crnih izdajica, pa kad ih narod bude čitao iz dna duše proklinjat će one koji su ta nečastna imena nosili, proklinjat će vas i uspomenu vašu, i proklinjani ćete biti i u hladnim grobovima, gdje nećete mira naći, jer i tamo, preko groba pratit će vas proklestvo hrvatskog roda, na kom počiniste izdajstvo. I neka, nek proklestvo prati crne izdajice. Prokleti bili za sve vjekove izdajice, zatrla vam se obečašćena imena!” (Chicago, Hrvatska zastava, 4. svibnja 1905.)

Tko ima uši, neka i danas čuje!

dr. Ante Čuvalo

Približava se kraj 2025. godine – jubilarne 1100. obljetnice krunidbe prvoga hrvatskoga kralja Tomislava. Koliko se naroda u svijetu može podičiti da su imali državu i kralja unatrag tisuću i sto godina?! Ne samo da su Hrvati tako davno imali kralja i državu, nego je hrvatska kraljevina u ovakvom ili onakvom obliku trajala sve do 1918., a samostalna i slobodna država Hrvatska i danas je tu! Istina, naša kraljevina/država kroz povijest je napadana i gažena, ali je „na tvrdoj stini” sagrađena. Tu je i tu ostaje! Hrvati se ne predaju!

Očekivalo se da će Hrvati u domovini i diljem svijeta ovu 1100. jubilarnu godinu obilježiti i uveličati na razne načine; da će državne i kulturne ustanove, škole i župe, selo i grad, sa zanosom proslaviti krunidbu prvoga hrvatskoga kralja. Ali kao da sami sebi ne vjerujemo da smo mi, Hrvati, imali međunarodno priznatu kraljevinu unatrag toliko stoljeća. K tomu, uvijek se nađu pametnjakovići koji su spremni sve što je hrvatsko (valjda je i njihovo) omalovažiti, nijekati, i „dekonstruirati” da bi sijali sumnje i „konstruirali” svoje mitove i zlonamjerne tvorevine.

Istina, tijekom ove godine bilo je nekoliko jubilarnih proslava krunidbe kralja Tomislava. Ali nije bilo ni blizu onoliko slavlja koliko 1925., tijekom proslave 1000. obljetnice toga povijesnoga događaja. Za razliku od ovogodišnjih svečanosti, ondašnje su bile mnogobrojnije, svečanije, i s mnogo više zanosa, u domovini i diljem svijeta.

Među proslavama 1000. obljetnice ima i jedna anomalija. Naime, Hrvati Pittsburgha i okolnih mjesta proslavili su tisućitu obljetnicu krunidbe prvoga kralja svih Hrvata 1903. godine. Ovdje ćemo pokušati dočarati tu „uranjenu” i iznimnu proslavu na temelju zapisa koje su nam ostavili očevidci. Također, nastojat ćemo dokučiti razloge zašto su Hrvati u Americi slavili 1000. obljetnicu krunidbe 1903., a ne 1925. godine.

Zamisao za proslavu 1000. obljetnice krunidbe kralja Tomislava rodila se 5. ožujka 1903., dok su tadašnji prvaci hrvatske naseobine u Alleghenyju (danas dio Pittsburgha) „uz kavicu” razgovarali o budućim društvenim djelatnostima među tamošnjim Hrvatima. Narod je ideju pozdravio i zdušno prihvatio.

Prvi radni sastanak za organiziranje proslave ove jubilarne obljetnice održan je 17. travnja 1903. u hrvatskoj dvorani u Alleghenyju. Na sastanak su došli vodeći ljudi iz Narodne hrvatske zajednice (od 1925. Hrvatska bratska zajednica) i iz tadašnje Hrvatske katoličke zajednice (utemeljena je u Bennettu 1902.; spominje se i kao Hrvatska katolička radnička zajednica i Hrvatska rimokatolička zajednica; pokretač joj je bio rev. Franjo Glojnarić, župnik, 1899. – 1905., mjesne župe sv. Nikole. On i suradnici osnovali su 1903. i Hrvatski kršćanski politički klub i izdavali novinu Hrvat. Urednik je bio dr. Milan Kovačević. Zajednica, Klub i novine djelovali su samo oko dvije godine.). Na tom sastanku prihvaćeno je da proslava bude održana 1. lipnja 1903. i naglašeno: „Tko je Hrvat, taj će na rad i doprinijeti sve moguće da se čim dostojnije proslavi tisućugodišnjica ujedinjenja Hrvata.”

U uži odbor za proslavu izabrani su sljedeći: dr. Milan Kovačević (predsjednik), Petar Pavlinac (podpredsjednik), Zdravko V. Mužina (prvi tajnik), Kosto Unković Mejić (drugi tajnik), Josip Šubašić (rizničar), vlč. Franjo Glojnarić i Katarina Ruklić (savjetnici). Da je proslava imala sveopću potporu,vidi se iz činjenice da su na tom (prvom radnom) sastanku sudjelovali predstavnici deset hrvatskih naseobina Pittsburgha i okolice. Širi odbor brojio je 52 člana. Izabrano je osam Hrvatica u poseban „Gospojinski odbor”. Također, na sastanku je dogovoreno da „čist dobitak od ove proslave bude namijenjen [novoutemeljenoj] školskoj ‘Družbi sv. Ćirila i Metoda u Sjedinjenim Državama’” (Družba je utemeljena u veljači 1903. kako bi se mogla otvoriti škola za hrvatsku djecu „na američkoj podlozi te širiti hrvatsku knjigu među američkim Hrvatima, a uz to priređivati takve zabave i predavanja, kojim bi opet svrha bila podignuti izobrazbu među američkim Hrvatima i među njima podržavati hrvatsku svijest u koliko se je to ticalo hrvatskoga podmlatka u Americi”. U roku od nekoliko mjeseci imala je 10 podružnica, ali vrući politički događaji u Hrvatskoj privukli su veliku pozornost Hrvata u Americi pa je Družba sv. Ćirila i Metoda izgubila na važnosti i u relativno kratkom vremenu prestala s radom.).

Zanimljivo je zamijetiti da je među članovima odbora bio i Jovo Ličina, Hrvat pravoslavac, kojega bi danas neki brojili među Srbe! (O odnosima Hrvata katolika i Hrvata pravoslavaca u Americi 1903. godine, iz gradića Rankina, Pa., iseljenik M. Š. piše sljedeće: „[M]ogu Vam javiti takodjer, kako većina naše braće Hrvata pravoslavnih živu s nama katolicima u ljubavi i slozi, prem imade i ovdje grčko-istočnih popova, koji bi htjeli pomutiti našu slogu, ali ufajmo se, da tim šugavim ovcama to neće poći za rukom, te nećemo nikome za volju pasti na lipak.” Tjednik Hrvat, Gospić, 15. ožujka 1903. Nažalost, „šugave ovce” su uspjele!).

Prvoga lipnja 1903. na svim hrvatskim kućama na ulici Ohio i drugdje u Alleghenyju vijorili su se hrvatski i američki barjaci. Hrvatska crkva sv. Nikole u Alleghenyju, u istoj ulici, bila je dupkom puna naroda koji je nazočio svečanoj sv. misi u 10 sati. Jedno izvješće kaže da se okupilo do dvije tisuće Hrvatica i Hrvata.

Sv. misu predvodio je vlč. Mato Matina (župnik u gradu Rankinu). Asistirali su vlč. Milan Sutlić (župnik u Clevelandu), vlč. M. Golubić (župnik grkokatoličke župe u Clevelandu), lokalni češki župnik, vlč. Fr. Šebik i vlč. J. Zalokar, iz slovenske župe sv. Barbare, Bridgville. „Krasnu je prigodnu propovijed” održao vlč. Mirko Kajić, župnik hrv. župe u Johnstownu, koja je objavljena u listu Hrvat, brojevi 13, 14 i 15, 1903. godine.

Nakon službe Božje slijedio je ručak. Zbog velikoga broja vjernika, objed je poslužen u dvije dvorane. Na oba mjesta tijekom ručka redali su se prigodni pozdravi i riječi dobrodošlice. Glavni tajnik priređivačkoga odbora, Mužina, dobio je više od stotinu telegrama u kojima su Hrvati diljem Amerike slali prigodne čestitke i domoljubna ohrabrenja.

U tri sata popodne, u Turner dvorani na So. Canal ulici, započeo je središnji dio slavlja. Osim glazbenoga dijela, raspored je bio sljedeći. U ime priređivačkoga odbora sve je pozdravio i zaželio dobrodošlicu J. Salopek, a potom su održali prigodne govore vlč. dr. Mato Matina, Petar Pavlinac (predsjednik Hrvatske narodne zajednice), Zdravko V. Mužina (jedan od utemeljitelja hrv. katoličke župe u Alleghenyju i Hrvatske narodne zajednice) i dr. Milan Kovačević (liječnik i književnik). Jedno izvješće svjedoči kako su „žive slike” priredile gospođa i gospojica Žibrat. „U sredini jedna povrh druge stajale su dvije djevojke držeći vijence u rukama; na lijevoj strani publike jedna je držala sliku oca i preporoditelja domovine Hrvatske, Dr. Ante Starčevića, a druga je držala sliku biskupa Strossmajera, mecene hrvatskog naroda. Povrh jedne i druge slike vile su držale lovorvijence. Ni kraja ni konca burnom odobravanju. Zastor padne. Nakon nekoliko časaka zastor se digao, a visoko na pedestalu ukazala se gospođa Žibrat, kraj koje je stajao Petar Pavlinac razvivši hrvatsku zastavu N.H.Z. Nastalo je neopisivo oduševljenje. Skladno je pjevao g. Knežević, a i S. Horvatić svojim solom, kojim je svima omilio. Navečer je bio ples, koji je potrajao preko pola noći.”

Sve tadašnje hrvatske novine u Americi pisale su o velikim uspjesima proslave 1000. obljetnice krunidbe kralja Tomislava u Alleghenyju, a priređivački odbor objavio je knjižicu od 16 stranica, na hrvatskom i engleskom, naslovljenu U spomen proslave 1000 godišnjice krunisanja hrvatskog kralja Tomislava, Allegheny, Pa., 1. lipnja 1903. Sjedinjene Države Sjev. Amerike. Uz dvije slike, knjiga sadržava: Proslov – prigodna pjesma dr. Milana Kovačevića; govor (na oba jezika) vlč. dr. M. Matine; govor (na oba jezika) Petra Pavlinca; govor (na oba jezika) dr. Milana Kovačevića i govor (na oba jezika) Z. V. Mužine.

Ta prva, „uranjena” proslava 1000. obljetnice krunidbe kralja Tomislava bila je vrlo svečana i uspješna, na zadovoljstvo organizatora i Hrvata u Americi općenito. Nameće se pitanje zašto su Hrvatima u Americi žurilo upriličiti tako dojmljivu proslavu prije nego što se u domovini o tome i govorilo. Ovdje ćemo donijeti nekoliko natuknica kako bismo odgonetnuli odgovor(e) na to pitanje.

Sve što se događalo u Hrvatskoj, dobro i loše, imalo je odjeka među hrvatskim iseljenicima u svijetu. Tako je bilo i krajem 19. i početkom 20. stoljeća. Iseljenici u Americi ne samo što su pozorno pratili nepravde i progone koje je hrvatski narod trpio pod režimom (1883. – 1903.) bana Khuen-Hédervárya, nego su uvijek bili spremni pomagati na razne načine svojemu napaćenomu narodu i domovini.

Početkom 1903. u Hrvatskoj su političke prilike postajale sve teže, a otpor režimu sve otvoreniji i krvaviji. Započeo je „skupštinski pokret”, dogodilo se ubojstvo Ivana Pasarića, oca troje djece, zbog paljenja mađarske zastave, redali su se prosvjedi protiv mađarizacije, ukidane su studentske stipendije, zbivala su se svakodnevna uhićivanja i ranjavanja, uveden je i prijeki sud u nekim kotarevima… To je izazvalo gnjev i bunt i među Hrvatima u Americi.

Svečano okupljanje 1. lipnja 1903. u Alleghenyju bilo je, dakle, istodobno proslava i prosvjed. To se lako uočava i iz prigodnih riječi Petra Pavlinca, predsjednika Narodne Hrvatske Zajednice, koji u svojem govoru naglasi: „Prolivena krv hrvatskog seljaka Ivana Pasarića, koji je branio pravo i čast naše domovine, vapi k nama, koji smo u zemlji slobode i ravnopravnosti, da je osvetimo bilo na koji način. Najčasnije za sada osvetiti ćemo je time, ako pritečemo u pomoć njegovoj razcviljenoj suprugi i kukavnoj dječici…”

Skupljana je i slana pomoć za obitelji poginulih, ranjenih i progonjenih, za studente i razne druge potrebite u domovini. U tu svrhu utemeljena je (u svibnju 1903.) udruga Hrvatska Narodna Obrana u Americi. Osim prikupljanja novčane pomoći, organizirani su i masovni prosvjedni skupovi u svim većim hrvatskim naseobinama, na kojima se govorilo ono što narod u Hrvatskoj nije smio. Na jednom od velikih prosvjednih okupljanja (29. svibnja 1903. u Alleghenyju, dva dana prije proslave krunidbe kralja Tomislava) bili su i predstavnici Poljaka, Slovaka, Čeha i Slovenaca. Tu je Z. V. Mužina, tijekom svojega vatrenoga govora, izvadio i potom zapalio mađarsku zastavu. To je dočekano s velikim odobravanjem, klicanjem i pjevanjem „Lijepe naše”. Na tom skupu prihvaćeno je da se pošalju dva izaslanstva u Washington D.C. Prvo državnomu tajniku SAD-a, a drugo u austrijsko poslanstvo, da bi tamošnje dužnosnike upoznali s Khuenovom autokratskom vladavinom te zatražili pomoć i zaštitu hrvatskih prava u domovini.

Nadalje, nisu iseljenici u Americi reagirali samo na progone i negativne pojave, nego, vapeći za hrvatskim jedinstvom, svesrdno su pozdravljali sve pokušaje suradnje hrvatskih oporbenih stranaka i neovisnih intelektualaca. I proslava 1000. obljetnice krunidbe kralja Tomislava odvijala se u žarkoj želji za hrvatskim političkim i nacionalnim jedinstvom. To se posebice vidi iz govora dr. Matine, koji je naglasio: „Sloga i ljubav naša stavlja na prestolje prvog kralja hrvatskoga Tomislava. Sloga i ljubav podala nam je umjetničke ruke, da od zlata i dragoga kamenja skujemo i satvorimo kraljevu krunu, te ju postavimo na glavu junačkomu hrvatskomu sinu Tomislavu… Kad je nestalo sloge i ljubavi nestalo je kovača krune hrvatske a nestalo je ujedno i hrvatske sreće.” I prizor dviju slika, Starčevića i Strossmayera, na pozornici koje su bile „okrunjene” lovorovim vijencima očito su bile poruka i vapaj „onima doma” da samo s ljubavlju i slogom možemo izboriti svoju slobodu.

Polovicom 19. stoljeća Hrvati počinju u većem broju pristizati u Ameriku, ponajprije u Kaliforniju, Louisianu i New York, a masovno useljavanje krenulo je krajem 1880-ih godina. Gdje god je bilo rudnika, tvornica i kamenoloma, bilo je i brojnih Hrvata.

Prve udruge za uzajamnu pomoć nosile su imena „Slavonic”, „Slavic”, „Illirian”, „Dalmation” i slično jer nacionalna svijest tih ljudi nije bila istančana (Sljedeći primjer ukazuje na nejasnoće identiteta među (nekim) iseljenicima toga vremena. Naime, novopridošli Hrvati rodom iz Kastavštine, Lošinja i nekoliko njih iz Dalmacije utemeljili su 1900. u New Mexicu potporno društvo “Majka Božja s Trsata”, odsjek 143 Narodne hrvatske zajednice. Nakon nekoliko mjeseci pridružilo im se već postojeće samostalno potporno društvo koje je nosilo ime „Slavensko primorsko društvo”. Uvjet ujedinjenja bio je da se zadrži i njihovo ime. Tako je nastalo „Slavensko primorsko družtvo Majke Božje s Trsata”, br. 143 NHZ. Službena odora bila je „slična onoj austrijske mornarice, nakićena hrvatskom krunom i trobojnicom”. Zastava je bila „amerikanska, koju kiti velika hrvatska vrbca, uz to se zaključilo na izvanrednoj sjednici, da se imade što prije dobaviti još velika hrvatska zastava.” Slavensko ime, hrvatska trobojnica i kruna, narudžba velike hrvatske zastave i boje austrijske mornarice! Očito, oni su osjećali da su Hrvati, ali vanjština je bila šarena. Nije bilo samostalne hrvatske države!) Ali pred kraj stoljeća, rastom broja novopristiglih Hrvata započinje i nacionalni preporod hrvatskih iseljenika u Americi. Naime, među novopridošlima bio je i jedan broj školovanih i nacionalno svjesnih ljudi, a neki su od njih zbog domoljubnih djelatnosti morali potražiti slobodu u Americi (npr. vlč. Mato Matina (1854. – 1905.), vlč. Davor Krmpotić (1867. – 1931.), Nikola Polić (1842. – 1902.), Zdravko V. Mužina (1869. – 1908.) i brojni drugi.) Zahvaljujući radu i upornosti tih pojedinaca ne samo da je hrvatska svijest naglo rasla nego su nicale i hrvatske organizacije, župe, škole, domovi, novine, zborovi, glazbeni sastavi… Udruživali su se u političke klubove da bi mogli biti čimbenik u američkoj politici i u humanitarne udruge da bi pomogli jedni drugima i potrebitima u Hrvatskoj. Imali su kulturna društva da bi čuvali i prenosili svoju kulturnu baštinu na mlađe naraštaje.

Jedna od tih organizacija bila je i Narodna hrvatska zajednica, utemeljena 1894. godine. Ona je 1903. imala više od 240 ogranaka i više od 16 tisuća članova (U tiskovini Svjetlo, Karlovac, od 6. rujna 1903. stoji „da HNZ broji 17 000 članova, ako li se pribroje i žene članova, to znači taj broj [je] 26 000. Ovo je najbrojnije hrvatsko društvo”. Iz toga se može vidjeti koliko je bio velik broj samaca!) Ali kad se uzme u obzir da je početkom 20. stoljeća u Americi bilo (računa se) oko 300 tisuća Hrvata, onda je taj broj premalen. Zato je i velika proslava 1000. obljetnice krunidbe kralja Tomislava bila usmjerena ne samo na jačanje nacionalne svijesti nego i na poziv okupljanja u zajedničke redove NHZ-a.

Predsjednik Zajednice, Pavlinac, na proslavi 1000. obljetnice krunidbe kralja Tomislava, u svojem je govoru istaknuo i ovo: „N.H.Z. imala je od početka pa i danas ima dvije glavne svrhe: podupirati svoje članove materijalno i moralno. Materijalno, da nastradali Hrvati u ovoj zemlji ne skapavaju i ne padnu u svojoj nesreći na teret državi. Moralno, da se u hrvatskim iseljenicima iza toliko stoljeća izrabljivanja u tudje svrhe probudi čista narodna svijest: da nauče svoje iz dna srca ljubiti, a tudje štovati ukoliko je štovanja vriedno; da može svaki sam pojmiti što znači biti slobodan čovjek u slobodnoj zemlji i kako treba tu slobodu cieniti i upotrebiti.”

Ban Khuen maknut je s banske vlasti u lipnju 1903. i odlazi u Mađarsku. U kolovozu te godine u Hrvatskoj započinje politika „Novog kursa” koja će (1905.) izroditi „Riječku rezoluciju” i hrvatsko-srpsku koaliciju. „Novi kurs”, „Rezolucija” i nesretna H-S koalicija oduzimaju dah zamahu nacionalnoga preporoda koji se odvijao među američkim Hrvatima tijekom desetak posljednjih godina 19. i prvih godina 20. stoljeća. Moglo bi se s pravom tvrditi da je jubilarna proslava 1000. obljetnice krunidbe prvoga hrvatskoga kralja u Alleghenyju bila posljednji veliki svehrvatski domoljubni izražaj iseljeničkoga preporoda među Hrvatima u Americi. U toj proslavi sudjelovali su konzervativniji i liberalniji intelektualci, simpatizeri Starčevića i Strossmayera, te vodeći crkveni ljudi i župe. Ali, s dolaskom politike „Novog kursa” i u iseljeničkim redovima nastaje domoljubna pomutnja, koju će srpske i projugoslavenske snage uspješno potpirivati i njome manipulirati.

Nadalje, u to se vrijeme pojavio i naglo jačao još jedan važan društveno-politički čimbenik koji je uspješno unosio razdor i ideološke sukobe među hrvatskim iseljenicima u Americi. Bili su to sljedbenici i pobornici socijalizma.

Naime, zbog Khuenova općega terora i zabrane sindikalnih organizacija, jedan broj zanatlija, naučnika i radnika, koji su bili članovi socijaldemokratske stranke (osnovane 1894.) ili pod njezinim utjecajem, pošli su iz Hrvatske tražiti slobodu u Americi. Nastanili su se u velikim industrijskim centrima, ponajprije u Alleghenyju i Chicagu. U početku su djelovali potiho i učlanjivali se u postojeće odsjeke Narodne hrvatske zajednice. Ali su se relativno brzo ohrabrili, počeli organizirati i glasno djelovati.

Slijedeći svoje uzore u Hrvatskoj i njihove upute, nisu promicali samo socijalizam, nego i „narodno jedinstvo”, odnosno jugoslavenstvo, i ateizam. Tako su već 1903. u Alleghenyju otvorili jugoslavenski klub i jugoslavensko obrazovno društvo te počeli „osvajati” odsjeke NHZ. U Chicagu su 1907. počeli izdavati socijalističke (navodno hrvatske) novine Radnička straža, kojima je prvi urednik bio socijaldemokratski aktivist Milan Glumac, Srbin rodom iz Bosne. Ideologija jugo-socijalizma dobro se uklapala u tadašnji radnički pokret u Americi i naglo se širila (i) među hrvatskim radnicima. Utjecaj jugo-socijalizma među Hrvatima u svijetu konačno je skončao 1990-ih, ali i nakon toliko tragedija domovinska ljevica danas skuplja krhotine propalog jugo-komunizma.

Politika „Novoga kursa”, H-S koalicija i nagli uspon djelovanja socijalista bili su važni čimbenici koji su pomutili domoljubno ozračje koje je dobrih desetak godina jačalo među hrvatskim iseljenicima u Americi i bilo svečano osvjedočeno na proslavi 1000. obljetnice krunidbe kralja Tomislava u Alleghenyju, Pennsylvanija.

Zašto baš 1903.?

Koliko smo mogli doznati iz tadašnjih izvješća o proslavi, Z. V. Mužina je kazao da je Tomislav postao knez 903. i bio okrunjen kraljem 925. godine. Dakle, proslava u Alleghenyju 1. lipnja 1903. bila je ponajprije usredotočena na ujedinjavanje hrvatske zemlje pod knezom Tomislavom, a ne na godinu njegove krunidbe. Kako je Mužina zaključio da je to bilo 903., ostaje zagonetno.

Istina, godine 1903. objavljen je roman Velimira Deželića, Prvi kralj, pa je i to moglo potaknuti ideju proslave krunidbe kralja Tomislava te godine. Slavko Pavičić u knjizi Hrvatska vojna i ratna povijest i Prvi svjetski rat. Split: Knjigotisak, 2009., str. 11. i 12., kaže: „Knezu Bijele Hrvatske Tomislavu (903. – 928.), kasnije prvom hrvatskom kralju, uspjelo je od Bijele Hrvatske stvoriti jaku silu na Jadranu.” Nije nam poznato na temelju kojega je to povijesnoga izvora ustvrdio.

Uostalom, nije važna godina, nego priznanje hrvatske kraljevske krune i države.

dr. Ante Čuvalo

Napomena

Članak je temeljen (ponajviše) na sljedećim izvorima: manuskript Jurja Škrivanića, čiju presliku posjedujem, a objavljen je u knjizi Povijest američkih Hrvata, Zagreb: Hrvatski svjetski kongres, 2011.; članak vlč. Bosiljka Bekavca (starijega), Naša Nada Kalendar za američke katoličke Hrvate, za običnu godinu 1930., Hrvatska Katolička Zajednica, U.S.D. Amerike; knjižica U spomen proslave 1000 godišnjice krunisanja hrvatskog kralja Tomislava, Allegheny, Pa., 1. lipnja 1903. Sjedinjene Države Sjev. Amerike. Presliku te knjige poslala mi je Maura Coonan, Assistant Archivist, Immigration History Research Center Archives, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis MN. Srdačno zahvaljujem Mauri i Institutu na ljubaznosti i pomoći.

___________________

Dodatak

Ovdje donosimo pjesmu koju je dr. Milan Kovačević (1869. – 1931.) napisao u čast krunidbe kralja Tomislava. Donosimo i govor vlč. dr. Mate Matine (1854. – 1905) na proslavi 1. lipnja 1903. u Alleghenyju. I danas bi njihove riječi trebalo pomno čitati!

___________________

Dr. Milan Kovačević

Proslov

U krvi svojoj zaguši se Rim; —

Nad drevnim hramovima,

Uzbiesnio je oganj, uzvitlo se dim,

Te propast bude puku i senatorima!…

A barbar dignu gordo svoje čelo

I nogom zgazi u prah,

Što gonilo je u strah

Kroz stoljeća čovječanstvo cielo.

Ko kakav bludnik zgurio se rod

Pompeja, Cicerona,

I, što bijaše nekadanje slave plod,

— Velebni luk — sad svjedokom je, vasiona

Gdje divlja četa kolo igra svoje,

Uz urlik gdjeno pjeva

I zalud na nju zieva

Ta vučica grozna s djece dvoje.

Al nije zato propao još sviet!…

Gle: tamo, gdjeno sjajno

Òbasjalo je sunce „od istoka cviet“ —

Il biser –: rimskog cara boravište bajno,

Predivni dvor, što poput basne niče,

Dá tamo, gdje na valu

Na jadranskomu žalu

Kò labud se ladja lako miče.

Sakupio se puk, da velik god

U sreći sada slavi

I, kad do kopna stignuo je zlatni brod,

Sav narod pade nice, u silnoj tad ljubavi

U mladenačkom žaru klicat stade

Na pozdrav zlatnom daru,

Što po svom poklisaru

Previernom puku papa dade.

Oj, koli divan bio je taj dar!

U duši puka toga

Usplamtila je radost i ponosa žar,

Jer dar taj jeste kruna, kojom sad mu svoga

Preslavno čelo Tomislava kralja —

Od hrvatske koj krvi

Zavriedio ju prvi —

Na duvanjskom polju krunit valja.

Kroz stoljeća je trajo divski boj,

Što hrvatsko ga pleme,

Za dom si novi vojevalo svoj

I njegova je krvca bila pravo sjeme,

Iz kog je nikla država mu jaka,

Da svatko njega časti

A klanja mu se vlasti

Na Adriji sinjoj zemlja svaka.

I, kladno sada zlatne krune sjaj

Sa kraljevske mu glave

Zablieštio je narod sakupljeni taj,

Tad Tomislav je stigo vršak svoje slave,

A gora, dol i more jeknu jekom

Od klika, što zaori,

Ko grom što zagromori:

„Oj, živila slava Tvoja viekom!“

Na četir’ strane sjeknu njegov mač,

Što znak nek bude svima,

Da nositi će poraz, prouzročit plač

Po cielom svietu puka svoga dušmanima,

A vojske silne oružje tad bljesnu,

Jer, rado će u poju

Vojevat š njim u boju —

I štitova sto tisuća tresnu.

Raširila se njihova je moć,

A slava sve do danas

Rasvjetljuje nam prošlost ko zvjezdica noć:

Jer divnu stvorili su domovinu za nas,

Poškropiv krvlju svojom prvi kamen

Prebajne zgrade one,

Gdje nikad ne utone

U zaborav junačtva im znamen.

I hrvatski dok živ nam bude rod,

Dok bude brat uz brata,

Viek slavit nam je radostni taj god:

Pred tisuć ljeta uskrs nas Hrvata!

I nek se vije crven—bielo plava

Ta zastava nam sveta,

A diljem cielog svieta

Nek ori se: Tomislavu slava!

___________________

Vlč. dr. Mato Matina

Govor

U ozbiljnim epohalnim časovima narodnoga života dolikuje svjesnom sinu majke domovine, da za koji časak sjedne na školske klupe, gdje korisno predavanje drži stara učiteljica ali vazda lijepa i mila, koja je na sveučilištu svega čovječanstva primila diplomu sposobnosti, a zove se po uzvišenom zvanju svojem „magistra vitae” a po imenu zove se „historija”, ili našim milim jezikom hrvatskim „povjest”.

Povjest nas nauča poznavati dogodjaje, a to je baš onaj naukovni predmet, kod kojega se imademo ozbiljno zamisliti, da mu shvatimo veliku važnost. Značajno je to, što se povjestni dogodjaji obično stavljaju u sasvim drugu kategoriju duševnoga narodnoga života, nego li u koji oni spadaju. Obično se tvrdi, da pojedinci stvaraju dogodjaje ili epohalne preokrete. To je krivo shvaćanje. Povjesnički dogodjaji su izlijev sveukupne nepokvarene narodne volje i uzrok javnoga života; a pojedine osobe su tek posljedice ili tvorine toga uzroka.

Nije na primjer istina, da je Napoleon stvorio francuzko carstvo; već je istina, da je slobodna volja francuzkoga naroda stvorila dogodjaj, koji je stavio carsku krunu na Napoleonovu glavu. — Narodnja volja bijaše dogodjaj, a Napoleon tek slučaj.

Duh Oliwera Cromwela, bio on, kako mu drago jak, nije bio stvoriteljem ujedinjenih republika: Englezke, Irske i Škotske. Ujedinjena narodna volja stvorila je ujedinjenje tih velikih republika, i stvorila je ujedno Oliwera Cromwela kao protektora ili ephora. Taj dogodjaj (a ne osobna krivnja) odrubio je okrunjenu glavu englezkomu kralju Karlu I.

Na novcu ove slavne države, gdje mi sada uživamo blagodati slobode, stoji napisano: „E pluribus unum”. Ko je to prvi dao urezati u zlatni i srebrni novac ovih država, pogodio je historički dogodjaj ove zemlje. Nije samo jedan čovjek rekao „Amerika Američanima” već je volja cjelokupnoga naroda zatražila, da bude „E pluribus unum”. — Volja naroda u ogromnoj zemlji četirijuh zona stvorila je od 49 država jednu državu „E pluribus unum”. Volja naroda bijaše onaj umjetni stolar, koji je sagradio blistavu stolicu za predsjednika saveznih država. Ujedinjena volja naroda postavila je prvoga predsjednika na tu slavnu stolicu. Niti prvi, niti ikoji drugi predsjednik nije stvorio saveznih država, već je savez narodnje volje stvorio prvoga predsjednika i stvara ostale.

Bilježimo ovu činjenicu, a po tom dajmo krila duhu svojemu, koj ne poznaje zapreka mjesta ni vremena. Neka poleti u mile one i slavne krajeve hrvatske. — Neka motri i rasudjuje što se je u domovini Hrvata zbivalo nazad jedne potpune tisuće godina! Što se je u maloj ali miloj hrvatskoj zemlji zbivalo onda, kada se ni u dvadesetoj descendenciji nisu rodili praroditelji onoga slavnoga muža, Kristofa, koji je obreo ovu veliku zemlju, u kojoj mi sada živimo? Što se je u nas dogodilo mnogo prije, nego li je noga istoga Erika Rande stupila na kopno Groenlandije? Sjaj divnoga hrvatskoga nakita rijesi grudi hrvatskih junaka. Gvozdeno oružje, osvjetlano slavnim pobjedama, što ih je izvojištila ne opisiva heroička hrabrost hrvatskih junaka, svjetlucao se o bedrima hrvatskih banova. — Duša sveukupnoga naroda pjeva pjesmu najdivnije melodije. Narod pjeva pjesmu, koju je sam napisao, umočiv pero svoje u crvenilo krvi srca svoga. Pjeva tu pjesmu melodioznu ali „forte”, hoteć da sav svijet čuje glas hrvatske duše: Sloga i ljubav naša stavlja na prestolje prvoga kralja hrvatskoga Tomislava. Sloga i ljubav podala nam je umjetničke ruke, da od zlata i dragoga kamenja skujemo i satvorimo kraljevsku krunu, te ju postavimo na glavu junačkomu hrvatskomu sinu Tomislavu. Taj dogodjaj imao je, a i sada imade svoj jezik, kojim je ne ustrašivo svemu svietu progovorio: Evo Ti hrvatski sine Tomislave hrvatske krune! Stavi ju na dičnu glavu svoju s uvjerenjem, da je kruna mandat narodne volje i ujedno simbol narodnje slave. Kralj je mandatar, ili zapovjednik, koji zapovjedati imade, da se zapovjed narodne volje savjesno ovršuje.

Blago bijaše stanje hrvatskoga naroda, dok se je ovaj glas narodnje hrvatske duše čuo i razumio. Kad je nestalo sloge i ljubavi nestalo je kovača krune hrvatske a nestalo je ujedno i hrvatske sreće. Nesloga hrvatska stavlila je hrvatsku krunu na glavu tudjinca. Tako je potamnila kruna hrvatska. Tako je potamnila i slava slavnoga hrvatskoga naroda. — Onda je nastao nenaravan pojav, gdje pojedinac nije učinak već uzrok javnomu životu.

U takovom nenaravnom položaju moćni pojedinac, ukupno narodno tijelo, u kojem ne diše složan duh, smatra za mekani vosak, od kojega po volji i hiru može učiniti figurice, kakove si umišlja njegova gospodska volja. Takova volja pojedinca, koj nije predstavnik volje ukupnoga naroda, stvara nesnosljive odnošaje. Danas Ti njegova „najmilostivija” volja podpiše dekret za prvoga ministra, a sutra ista ova „najmilostivija” volja šalje ti svilen užinac, da te zadave na prvim vješalima.

Danas ste slavni Zrinjski i Frankopani, najslavniji i najdičniji junaci „mojega” hrvatskoga kraevstva. Vaša sablja odbijala je vazda junačkom snagom oštricu turske sablje, da ne dodje do „previšnjega” vrata mojega. To je danas, a sutra tupi austrijski švabski krvnik tupim orudjem rubi slavne i ponosite hrvatske glave hrvatskih mučenika Zrinjskoga i Frankopana. Za uzdarje prezrev nas!

Danas junački sin hrvatski Jelačić sa junačkim narodom hrvatskim prelazi rijeku Dravu, da krvlju svojom i naroda svoga spasi i život kralja i njegovo prestolje od bahatoga Magjara, koj je kralja skinuo s kraljevskoga prestolja. Sutra se oglasuje taj isti kralj te magjarskom skvrnitelju krune i prestolja daje premoć i tiransku upravo vlast nad hrvatskim osloboditeljem krune i kraljevske osobe.

Danas u ljepoj našoj zemlji Hrvatskoj hladni tudjinac smjelo i drzovito gazi načelo naravi, načelo istine i pravde. Gnjusan ovaj posao, koj je u diametralnoj opreci sa visinom moderne naobrazbe, ovršuje ledeni taj tudjinac odvažno i okrutno; jer opaža na svoju sreću, koja je nesreća hrvatskoga naroda, da ne dolazi u sukob sa snažnom složnom voljom cijeloga naroda. Braćo moja hrvatska! Ovako nebi smjelo dulje i dalje biti! Što jest tako, sami smo si krivi. Žalosno je, što nas bije tudja ruka, al je još žalosnije, što nas naša vlastita nesloga stavlja na ovu krvavu mrcvarnicu.

Oživimo stoga u sebi duh slavnih svojih pradjedova hrvatski. Oživimo u sebi duh, koj je živio u slavnom narodu hrvatskom prije tisuću godina, koj duh je za svojega kralja krunio hrvatskoga sina Tomislava.

Složan, živi duh ukupnoga, ponosnoga naroda hrvatskoga stvorit će jamačno dogodjaj, koj će skupocjenom krunom ovjenčati dičnu glavu trojednoga kralja hrvatskoga, koj se ne zove Tomislav, već „jedinstvo, samostalnost i sloboda” plemenitoga hrvatskoga naroda.

![]()

![]() Prilog je dio programskoga sadržaja “Događaji i stavovi”, sufinanciranoga u dijelu sredstvima Fonda za poticanje pluralizma i raznovrsnosti elektroničkih medija.

Prilog je dio programskoga sadržaja “Događaji i stavovi”, sufinanciranoga u dijelu sredstvima Fonda za poticanje pluralizma i raznovrsnosti elektroničkih medija.

Zagreb: Chicago: CroLibertas Publishers & Zagreb: Hrvatko žrtvoslovno društvo, 2018;

predstavljana u Zagrebu, 24. listopada 2018. u 19 sati u dvorani „Vijenac“

Izlaganje dr. sc. Stjepana Matkovića

Zadovoljstvo mi je večeras biti u ovome okruženju i ukratko govoriti o temi koja je još uvijek nedovoljno istražena u historiografiji, a zbog njene važnosti ne bi je trebalo zanemariti. Zbog toga mislim da je napor kolege Čuvala vrijedan prilog poticanju rasprave o tome što se doista dogodilo u Odesi i na Crnome moru. I to ne samo zbog ponovnog objavljivanja u cjelovitom obliku jedne saborske interpelacije u kojoj se po prvi put i uz navođenje niza pokazatelja iznose podaci i tumačenja o okolnostima koje su dovele do počinjenih grozota nad hrvatskim vojnicima, nego i zbog drugih materijala kao što su uvodni tekst renomiranog profesora Banca, malo poznata svjedočenja Milana Špoljareca i Antona Špehara, bibliografija objavljenih tekstova koju je sastavio Ivan Miletić, kao i vrlo dobar članak Đure Grlice, izvorno objavljen 1984. u čikaškom tjedniku Danica.

Podlogu za ovu tragičnu priču iznio je zagrebački odvjetnik Aleksandar Šandor Horvat, rodom iz Sutinskih Toplica, u svojoj interpelaciji na saborskoj sjednici od 6. srpnja 1918., dakle nešto manje od četiri mjeseci prije raspada Austro-Ugarske i nadolazećeg stvaranja jugoslavenske države. Podsjetio bih da je riječ o prvaku tadašnje Stranke prava, jedne od najjačih oporbenih stranaka u sabornici koja je bila konzistentni zagovornik rješavanja hrvatskog nacionalnog i državnog položaja u sklopu Habsburške Monarhije i načelno odbijala prihvatiti bilo kakav tip jugoslavenske ideologije, navlastito one njene varijante koja je išla za osnivanjem državne tvorbe s Kraljevinom Srbijom na ruševinama Austro-Ugarske, objašnjavajući da je to jedini način da se Hrvati izvuku iz „crno-žute tamnice naroda“. U tom smislu, Horvat i njegova skupina pravaša izražavala je svoju lojalnost prema dinastiji, očekujući zauzvrat ustrojavanje jedne državne jedinice koja bi ujedinila hrvatski narod. Zbog takvog stava, koji je počivao na uvjerenju da će Beč i Budimpešta morati shvatiti iz vlastitih interesa emancipacijski program pravaštva, pripadnici su ih jugoslavenske struje u hrvatskoj politici tendenciozno nazivali separatistima i izdajnicima koji narušavaju iluziju o narodnom jedinstvu Hrvata i Srba. Horvat je tijekom 1918. bio u audijenciji kod kralja Karla ne bi li ga uvjerio u ispravnost hrvatskog stanovišta. No, bilo je već prekasno. Bliska budućnost pokazat će tako da je upravo navedena jugoslavenska skupina pod geslom bratske jednakosti bila kratkovidna jer je svjesno ili nesvjesno, ovisno o kome je bila riječ, sudjelovala u pripremi terena kojim je nametnut novi oblik prevlasti i prevage nad Hrvatima. Da je bilo tako progovorit će kasnije i brojni akteri ovih promjena.

Na temelju uvida u sadržaj Horvatove interpelacije i nekih drugih svjedočanstava može se zaključiti da je pravaški prvak došao do izvornih materijala o počinjenim zločinima preko Crvenog križa, odnosno najviše preko onih zarobljenika u Rusiji koji su pripadali ili simpatizirali njegovu stranku. Na taj su način ostala sačuvana svjedočanstva malih, običnih i nezaštićenih vojnika koji su platili najvišu cijenu zato što se nisu dali uvući pod srpsku komandu. Neki od zlobnih komenatora ove knjige će zasigurno naglasiti da je među informatorima s terena bio i Mirko Puk, glinski odvjetnik i kasnije istaknuti član ustaškog vodstva za vrijeme Drugoga svjetskog rata, zbog čega će poput nekih saborskih zastupnika iz 1918. tvrditi da su podaci iz interpelacije bili bajka. No, kad pročitamo zapis jednog drugog Horvata, poznatog publicista Josipa Horvata, koji je također bio u ruskom zarobljeništvu i zapravo je imao razvijene osjećaje prema jugoslavenskom idealizmu, onda dobivamo još jednu potvrdu o zločinima u Odesi. Josip Horvat je zapisao: „Sve je to bilo nalik na nevjerojatan sablastan san. Prva je misao: da je sve to pakostan falsifikat, možda iz Pukove kuhinje, no žigovi su ispravni, rukopis je poznat (…). Nema razloga za ne vjerovati. Razgovori su sad postali mučni. U atmosferi se nadâ iznenada otkrilo jezivo bespuće. Od političke strane krize gora bijaše čisto ljudska strana te dobrovoljačke drame. Dosad je za omladinu Austrija bila pojam despocije, tamnice, simbol joj bijaše u tim godinama vojarničko dvorište s kestenima, o koje vješaju nepokorne vojnike. Jugoslavenstvo bijaše pojam slobode, čovjeka, poštivanje prava ljudskoga dostojanstva, a sad eto: batine, strijeljanje, nepriznavanje političkog uvjerenja.“

Aleksandar Horvat bio je jedan od aktera rasprave o Odesi koji je želio razotkrivanjem toga slučaja otvoriti oči onima koji nisu vjerovali što može uslijediti nakon rata, ako se ne osiguraju hrvatska prava. Ako se vratimo na početak Prvoga svjetskog rata, onda se susrećemo s aktivnostima emigrantskog Jugoslavenskog odbora u čijim su redovima istaknutu ulogu imali oni hrvatski političari koji su, suprotno Horvatu i njegovoj frankovačkoj družini, otvoreno zagovarali rušenje crno-žute Monarhije i stvaranje integralne jugoslavenske države. U tom im je smislu rat išao na ruku jer se, kako su sami govorili, „jugoslavensko pitanje moglo riješiti u velikom historijskom momentu“. Da bi potvrdili svoj utjecaj morali su pokušati izvršiti i zadaću okupljanja dragovoljaca i ratnih zarobljenika radi stvaranja vlastitih oružanih snaga. Dragovoljci su trebali biti dokaz o vojnom pružanju otpora Austro-Ugarskoj i njenim saveznicama, a svoju dodatnu notu imali bi i u kontekstu kraha srpske vojske krajem 1915. godine, čime bi upravo vojska iz hrvatskih i slovenskih zemalja postala ključan promicatelj jugoslavenske ideje.

Na tom ispreplitanju političko-vojnih pitanja vidljiv je korijen zločina koji su izvršeni u Odesi i njenoj okolici. Načelno je ideja vodstva Jugoslavenskog odbora bila razumljiva jer je polazila od nakane da se organizira južnoslavenska vojska izvan granica Monarhije koja bi imala svoje vojno zapovjedništvo i u datom bi se momentu ponovno vratila u svoje krajeve. Do tog momenta ona bi se mogla boriti na Zapadnom (francuskom) bojištu ili na dijelu Solunskog (makedonskog) bojišta protiv Nijemaca i Bugara, ali u svakom slučaju ne bi išla u sukobe s austro-ugarskim postrojbama u kojima su vojevali Hrvati. Međutim, sve se odvijalo na sasvim drugačiji način. Savezništvo sa susjednim zemljama koje su proglašavale svoje ratne ciljeve na račun Hrvatske imalo je svoju cijenu. U takvim okolnostima pokazalo se da je proklamirano ujedinjavanje s Kraljevinom Srbijom bilo ostvarivo samo uz kombinaciju pristajanja na diktate i popuštanja. Srpskom državnom vrhu nije odgovaralo da Jugoslavenski odbor drži svoje oružane snage jer je Srbija trebala biti u očima međunarodne politike jedini čimbenik u južnoslavenskom pitanju koji ima pravo na status pobjednika i nositelja „oslobođenja“. Priče o federalizmu kao jedinom mogućem okviru za ravnopravnost u jugoslavenskoj tvorbi nisu imala uporišta u stvarnosti. Prevladala je osnova srpskog državnog vrha koja je vještim iskorištavanjem jugoslavenske propagande provodila svoje ideale i uspješno djelovala na unutarnju dezintegraciju Habsburške Monarhije. O tome da su se stvari počele krivo odvijati svjedoče nam i pojedini predstavnici Jugoslavenskog odbora kojima je postalo jasno da jugoslavenska formula ne će spriječiti srpsku stranu od nametanja njenih težnji.

Slučaj u Odesi, kojim se večeras bavimo, odnosio se na zarobljenike austro-ugarske vojske iz redova raznih pukovnija – hrvatskih, slovenskih i bosansko-hercegovačkih, a jednim manjim dijelom i čeških – koje je ruska vojska zarobila na bojištu ili su bez borbe pobjegli na rusku stranu. Iz tog kontingenta – prema većini pisaca radilo se o otprilike 200.000 vojnika – nastojali su i srpska vlada i predstavništvo Jugoslavenskog odbora u Petrogradu, uz odobrenje službene Rusije, stvoriti tzv. dobrovoljačku diviziju koja je prvo vrijeme nosila isključivo srpski naziv. Od predstavnika Jugoslavenskog odbora traženo je da nagovaraju zarobljenike da pristupe toj diviziji, a sve ostalo je bilo prepušteno srpskom vojnom zapovjedništvu. Nagovori nisu urodili plodom tako da je najveći broj bio prisilno mobiliziran. Od samih početaka dobrovoljačke divizije vidio se nemar prema okupljenim vojnicima koji su bili slabo opremljeni i hranjeni. Zabilježeni su i primjeri zlostavljanja hrvatskih vojnika koje je provodio zapovjedni kadar srpskih oficira pristiglih s Krfa. Zapovjednik Stevan Hadžić nastojao ih je pak čim prije poslati u borbu protiv bugarske i njemačke vojske u Dobrudžu. Te su postrojbe tamo otišle i doživjele ogromne gubitke. Glavni predstavnik Jugoslavenskog odbora u Rusiji Ante Mandić u svom je izvješću tada zapisao: „Odbor se dosada nije ni malo brinuo u opće za rad u Rusiji, a po svoj prilici i za odred, nije nam ni na pisma, proste pristojnosti radi, odgovaro, a kamo li podržavao. I pri tome je trpio i njegov i naš ugled. ali to je nuzgredno. Glavna stvar je ta, da je poginulo toliko hiljada ljudi bez svake koristi našom krivnjom radi toga, što nijesmo na nje mislili, što se nijesmo za njih brinuli, što smo ih ih prepustili samovolji ljudi, koji u njima ne vide drugo nego sredstvo da lično briljiraju. (…) Za to sam ja odlučno protiv toga, da se naši dobrovoljci okupljaju u takove svrhe. Još više: ja sam mnijenja da odbor nema ni najmanje pravo, da lahkoumno stavi na kocku život tolikih zemljaka, ako nema absolutnih garancija, da je korist, koju će opća naša stvar imati, biti dostatan ekvivalent za gubitak ovih naših života. U Odesi počinjen je nad odredom zločin, inače se ne mogu izraziti. A ako odbor ostane kod svoje dosadašnje taktike prema njemu, to je jasno, da postajemo i mi svi direktni sukrivci tog zločina.“

Nakon povratka s tog ratišta krenula je akcija za stvaranjem druge dobrovoljačke divizije, koja bi zajedno s ostacima one prve tvorila jedinstveni korpus. Pri tome je dolazilo do nasilnog uvrštavanja u redove „nedobrovoljnih dobrovoljaca“. Loši postupci prema vojnicima i odbijanje polaganja prisege kojom bi se priznala odanost srpskoj dinastiji izazvali su, kako su to u duhu prikrivanja o razmjerima počinjenih zločina pisala službena izvješća, krizu koja je bila okončana odlaskom jednog većeg broja časnika i vojnika hrvatskog i slovenskog porijekla. Oni su u svom memorandumu upućenim ruskim vlastima izjavili da su se u ime ujedinjenja počinila „najgroznija nasilja i zločini: grabeži, izbijanja, mučenja, čak ubijstva, počinioci koji su ostali nekažnjeni.“ Tako je bio, kako bilježi najveći broj izvora, stvoren tzv. disidentski pokret. Međutim, u tim izvorima nema konkretnijih podataka o spomenutim nasiljima i zločinima, izuzevši lapidarno priznanje o incidentima. Više autora doduše piše o spontanoj pobuni ili nemirima protiv polaganja prisege srpskom kralju, kada su srbijanski vojnici ubili trinaest vojnika i ranili još niz drugih (događaji na Kulikovom polju). U tom kontekstu, kada se slučaj više nije mogao zataškati, srpsko vojno zapovjedništvo je odmah osudilo tzv. disidente, tvrdeći da je riječ o protuakciji „separatističke struje Frankovaca u Hrvatskoj“ i Krunoslava Heruca, jednog poznatog Hrvata iz Petrograda na čelu petrogradskog društva Križanić, koju je pak navodno podržavala ruska vlada na čelu s Borisom Stürmerom. Kao što je to bio česti slučaj u povijesti, Hrvati su proglašeni „oruđem u tuđim rukama“. Svi su počinjeni zločini negirani tako da se samo izvještavalo o „incidentima“ i „glavoboljama“ vojnih i civilnih zapovjednika. Na kraju je prevagnulo Pašićevo stajalište da su srpski oficiri jedini bili opunomoćeni za rad s dobrovoljcima, a vodstvo Jugoslavenskog odbora moglo se zadovoljiti time da je Srpski dobrovoljački korpus naknadno preimenovan u Dobrovoljački korpus Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca.

Podsjetio bih i na zapis Ivana Meštrovića koji je bacio dodatno svjetlo na postupak tadašnjeg razvrstavanja dragovoljaca, istaknuvši slabo poznat odnos prema muslimanima iz Bosne i Hercegovine: „Kod Bosanaca je bio drugi postupak. Izdvajalo se katolike, a ostale se pitalo: „Jeste li Bosanci?“, pa su onda trebali biti svi dobrovoljci. Kad su se muslimani počeli buniti, da oni nisu Srbi, onda ih se izdvajalo i „jednim posebnim načinom osvjedočavalo“. Kakvo je to osvjedočavanje bilo, pričao je koji mjesec kasnije neki Semez [riječ je o Dušanu Semizu], pravoslavac iz Bosne, komu je ta „misija za Bosance“ bila povjerena. „Koji Turčin nije htio (a malo ih je bilo od neškolovanih, koji je htio), sjekle su se glave sjekirom, a drugi, kad su vidjeli, pristajali su, Boga mi.“ Pri tom su mu pomagali neki „osvešteni“ muslimani“.

Isto tako, podsjetio bih i da je Aleksandar Horvat na početku izlaganja svoje interpelacije naznačio da pobija gledišta u korist jugoslavenske ideologije koja je ranije u sabornici iznio zastupnik Živan Bertić, odvjetnik iz Zemuna. A Bertić je doista jedan od primjera brojnih hrvatskih lutanja. Kao otvoreni protivnik austro-ugarske hegemonije želio je tijekom Prvoga svjetskog rata da se ostvari slom Habsburške Monarhije. Put ga je odveo u redove onih koji su podržali stvaranje jugoslavenske države. Nakon rata i stečenih iskustava zabilježio je u svojoj brošuri Hrvatska politika (Zagreb 1927.) kako se u stvari odvijala promjena državnog ustrojstva: „(…) uskoro medjutim dodje svršetak velikog rata, njegova [Lorkovićeva] grupa ne imadjaše više ni vremena ni uslova da se pojača do kakve vodeće uloge, i tako dočekasmo svršetak rata razbijeni, nespremni, nesložni i rastrovani kao nikad u historiji. Bjesmo u toj slabosti namamljeni sladkim riječima u Beograd i ondje nemilice pogubljeni kao ćurani na političkom stratištu.“ Slično tome govoriti će i pisati mnogi drugi akteri pokreta za stvaranje jugoslavenske države poput Ante Trumbića, Ivana Lorkovića ili Dragutina Hrvoja, ukazujući na svoje slabosti u prijelomnim trenucima.

Da zaključim. Zločini u Odesi su istiniti događaj koji bolno pokazuje žalosne sudbine vojnika o kojima, da nije bilo Horvatove interpretacije, vjerojatno ne bi više ni bilo govora. Vinovnici zločina su više-manje jasni, a počinitelji su očito imali podršku vojnog vrha srpske vojske. Ostaje, kao i u mnogim drugim slučajevima, otvoreno pitanje broja žrtava. Točan broj stradalnika nikada nije ustanovljen. Moram priznati da mi se procjene o broju žrtava koji se kreću u rasponu između 10.000 i 30.000 za sada čine previsokima i neka buduća, sustavna istraživanja trebala bi nas dovesti do utvrđivanja približno stvarnog broja palih vojnika. U svakom slučaju, na svima nama je da pronađemo način kako ugraditi žrtve iz Odese u našu kulturu sjećanja. Još jedanput čestitam kolegi Čuvali na objavljivanju ove knjige i poticaju da se ne zaborave tragični događaji iz Prvoga svjetskog rata.

S lijeva na desno: Ante Čuvalo, Tomislav Jonjić, Stjepan Matković, Hrvoje Hitrec, Ivo Banac, stoji Ante Beljo

In the year 118 B.C., Romans conquered the eastern shores of the Adriatic Sea and immediately established the province of Illyricum, named after an Indo-European people who lived in the area. The Roman army and government, however, did not have a lasting peace in the province. The Illyrian tribes, led by the Dalmatae, organized a rebellion soon after the conquest. Its center was in Daelminium, today’s Duvno in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Numerous rebellions against the Roman rule followed until 35 B.C., when Octavian (Augustus) came with a strong army and reinforced the Roman hold over the province. But even under Octavian’s grip, the Illyrians organized a major revolt in the year 6 A.D. The ferocious struggle lasted three years under the command of Bato, leader of the Illyrian tribe Daesitiates. The rebellion was crushed, and, in due time, Illyricum was divided into two separate provinces, Pannonia in the north and Dalmatia in the south.

The Illyrians accepted the Roman culture, language, religion, customs… and were Romanized in a relatively short period of time. On the other hand, the Romans built towns, roads, amphitheaters, and military camps… and expanded the empire to the north and east. Salona (Solin, near Split), the main city of Dalmatia, became known as a “miniature Rome.”

Spread of Christianity

Christian communities were established in Dalmatia and Pannonia in the first century after Christ. St. Paul states that he preached the Gospel “from Jerusalem and as far round as Illyricum.” (Romans 15:19) It cannot be stated for certain whether Paul means that he has preached the Gospel in Illyricum or that he has gone as far as the borders of that Roman province. However, an old tradition claims that Titus, a disciple of St. Paul, was the one who came to Illyricum to preach the Good news of Jesus.

It is known for certain that there was a Christian community with a bishop in Salona in the second half of the 1st century A.D. The best known bishop of Salona from the early times of Christianity was Duimus (Dujam, Duje) who, with a number of other Christ’s followers, was martyred in 304 A.D.

As it happened in other parts of the Roman Empire, many Christians were killed in Illyricum. The two best-known names among the martyrs are those of St. Duimus (Dujam) in Dalmatia (martyred in 304 A.D.) and St. Quirinus, bishop of Siscia/Sisak in Pannonia (martyred in 309 A.D.).

Christians were victims of Emperor Diocletian’s persecutions. The emperor was born in the city of Diocleia, province of Dalmatia, and after he abdicated the throne in 305 A.D., he returned to his native land. He built there a grandiose palace that is today the core of the city of Split in Croatia. Ironically, his mausoleum is today a Catholic cathedral. Another Dalmatian-born emperor, Constantine the Great, granted freedom to the Church, and Christianity rapidly spread throughout the empire, including the provinces of Dalmatia and Pannonia.

Monastic life in the Roman Illyricum

The earliest known monks who lived on the eastern shores of the Adriatic were Marin and Leon. They lived on the island of Rab at the end of the third century. Approximately at the same time, a monk named Felix lived near Salona. He was a victim of Diocletian’s persecution and became a well-known Christian saint.

Most of the historical knowledge about monks in this area of the Roman Empire comes from the writings of St. Jerome (c. 347-419 or 420), who was born in Stridon, province of Dalmatia. Although he lived most of his adult life in Rome and the Holy Land, he did pay attention to what was happening in his native land, especially concerning the monastic life there. For example, around 396 A.D., Jerome wrote to his friend, Bishop Heliodor (Heliodorus), also born in Dalmatia and who became a monk himself later in life, that his nephew Nepolitus wished to live a monastic life on the Dalmatian islands. Also, we know from Jerome’s other letters that his friend, monk Bonosa, lived on the Adriatic islands.

Around the year 405 A.D., Jerome praised his friend Julian for helping monks to build new monasteries on the Dalmatian islands and he recommended that Julian himself embraced monastic life. Clearly, there were not only individual monks living solitary lives on the islands but also groups of monks living in monasteries. Because of a pleasant climate, isolation, and safety, the Dalmatian islands were ideal places for monasteries and monastic life.

Furthermore, Hezihia (Hesychius), archbishop of Salona (405-426), indicated that numerous monks lived in his diocese at the time. Namely, in a letter to the pope, he asked for advice on how to deal with monks who were impatient to be ordained to the priesthood. Also, a regional church council in Salona (530 A.D.) forbade monastic superiors (abbots) to spend too much time outside the monastery walls because such practice diminished monastic discipline. Approximately from the same time, an inscription near Salona marks the burial place of Peter the monk, servant of Saint Peter. In the year 512 A.D., the pope addressed a letter to the bishops, priests, and monastic superiors and the people of Illyricum asking them to remain faithful to the traditions of the Roman Church.

The above points clearly indicate that the Church and monastic life flourished in the province of Illyricum during the centuries after the end of the persecutions (beginning of the 4th century) and before pagan Slavs, namely Croats, appeared on the eastern shores of the Adriatic in the 7th century.

The first contacts of Croatians with Christianity

In the year 610 A.D., the Byzantine Emperor Heraclitus, attacked from the northwest by the Avars and from the east by the Persians, enlisted the help of the Croatians, who had organized their state, known as White Croatia, on the other side of the Carpathian Mountains (today parts of Poland, Slovakia, Czechia, and Ukraine). After the expulsion of the Avars, the emperor, by a special pact, permitted the Croatians to take possession of the outlying Roman provinces of Dalmatia and Pannonia.

In the year 641 A.D., Pope John IV, who was born in Dalmatia, came in contact with the newly arrived Croatians on the eastern shores of the Adriatic Sea. Namely, he sent Abbot Martin to ransom some captive Christians and collect relics of the local martyrs from the pagan newcomers. This visit marks the first known contact between the Roman church and Croatians, as well as the beginning of the efforts of Rome to reestablish Christianity and religious institutions after they were devastated by the newcomers. All of the early papal delegates and missionaries on the eastern side of the Adriatic were Benedictine monks. Besides Abbot Martin, among them there were men by the name of Gottschalk, Mayhard, Teuson, Gerard, Gebizon, and others.

The religious and political relations with Rome evolved so fast that in 679 A.D., the Croatians entered into a special treaty with Pope Agathon, by which they promised, they would neither raid nor appropriate neighboring lands. In turn, the Pope assured the Croats, “If they were invaded, God would be their protector, and St. Peter would lead them to victory.”

First known Benedictine monasteries

The Benedictines were the first who brought Christianity to the newly arrived Croatians, but there are no known historical documents that would indicate the exact year when the first monasteries were established among the Croatians. However, most historians agree that the first known such monastery dates from the beginning of the 9th century. Possibly some monasteries were founded earlier, but so far there is no proof of that.

It is believed that at the beginning of the 9th century, Duke Višeslav was baptized by a Benedictine abbot in the town of Nin, which was the first political and religious center of the Croatian domain along the Adriatic coast, and that a Benedictine monastery was established in the area. The second monastery, for which there is certain evidence, was built during the reign of Duke Trpimir (845-864). It was located in the vicinity of Solin (near Split).

When Croatian lands fell under Frankish rule (beginning of the 9th century), a number of new Benedictine monasteries were established, and, in accordance with Frankish customs, the Croatian dukes gave major support to Benedictines ― new monasteries were built, and land grants were made.

The first known Benedictine monastery in Istria, a northwestern province of Croatia, existed in 860 A.D. The monastery and its church were dedicated to Saint Mary de Cereto near Pula. Thus, four known Benedictine monasteries in Croatia date from the 9th century. Perhaps, there were some other such monasteries, but (for now) that cannot be claimed with certainty.

In the 10th century, monasteries and monastic life increased rapidly, especially toward the end of the century when Croatia became an independent kingdom. There were more than 30 Benedictine monasteries in the country in the 11th century. The peak of the monastic growth was reached in the 13th century. Croatians had more than 60 monasteries at that time. However, from that point on the number of Benedictines and their active monasteries began to decline.

The reasons for the decline of Benedictines in Croatia were similar to those in Western Europe. Mainly, the appearance of new religious orders, namely the Franciscans and Dominicans. In addition, the Hungarian rulers, with whom the kingdom of Croatia shared a royal union, did not have an interest in supporting monasteries in Croatian lands because the monasteries were not only religious but also cultural centers and had an important social and political sway.

The decline of Benedictines in the Croatian lands was so great that at the beginning of the 19th century there were only four active monasteries. Even those four were closed in 1807 and 1808, and the Benedictine monks were banished by the French imperial administration that controlled a large part of Croatia at the time. Towards the end of the 19th century, some Italian and German Benedictines tried to organize new communities in Croatia but with limited success. Those well-intentioned individuals returned to their native lands after the First World War. However, in the mid-1960s, a new Benedictine male community sprouted by the efforts and dedication of a few native men. The ruins of an old monastery on the island of Pašman were repaired, and the centuries long tradition of Benedictine monks was revived in Croatia.

Cultural activities

The first centers of learning among the Croatians were the result of the Benedictine mission. The cathedral schools that emerged in time were also under the sway of the Benedictine monks.

Documents from the time of the first Croatian king, Tomislav (crowned in 925 A.D.), bear witness that Pope John X urged the nobility to send their children to the Benedictine schools to learn the Latin language. A regional Church council in Split (925 A.D.) instructs all to send not only their children but also servants to monastic schools.

Furthermore, the first Benedictine monastery for women opened in the 10th century. By the 13th century their number grew to about twenty-five. A number of such monasteries had schools for girls in which young women were taught, besides reading and writing, mainly sewing, weaving, and other practical trades.

It should not be forgotten that the Benedictine schools were free of charge and that the monasteries of both genders received pilgrims and travelers, had shelters for the homeless, and on certain annual holy days and feasts gave gifts of foodstuffs. The charitable works were an essential part of Benedictine life.

The earliest books among the Croatians were transcribed or written in Benedictine monasteries. Every monastic community had a library and librarians, scribes, and writers. The Benedictine scribes and writers were also in the service of local bishops, churches, and nobility. A monastery that had the best writing equipment and the largest number of scribes in Croatia was the abbey of St. Krševan in Zadar.

Benedictines and liturgy in the Slavonic language

Most of the Benedictine monasteries along the Adriatic Sea coastline, especially in its northern part, used the old Slavonic language in the liturgy from the earliest times. The oldest document that bears witness to this fact dates from the year 925 A.D. Namely, in that year, as mentioned earlier, a regional church council was held in Split, and at the council, bishops forbade the use of the Slavonic language in the liturgy except in monasteries. It means, therefore, that this language was in use for a longer period of time, at least in certain parts of the country and in some of the Benedictine monasteries. By implication, the use of Slavonic in liturgy had a strong tradition; otherwise, Rome would have banned it altogether.

One of the most important bishops in the Croatian political and religious life of the time was Grgur of Nin. He was a Benedictine monk and a fighter for the use of the Slavonic language in liturgy. Because of his steadfast stand on the language issue, he was transferred from Nin to the town of Skradin, and his influence was greatly limited. The struggle for the Slavonic liturgy, however, continued. Towards the end of the 10th century, a bishop and a Benedictine monk went to Rome to argue the case of the use of the Slavonic language in sacred liturgy.

Numerous liturgical books and documents were written in the old Slavonic language and Glagolitic script. In the middle of the 13th century, the pope reaffirmed the law that some of the monasteries could use the Slavonic language in the liturgy “according to the customs of their predecessors.”

In the 14th century, Czech king Karlo IV, with the help of the Croatian Benedictines, introduced the Old Slavonic liturgy in the Abby Emaus in Prague. Scribes from monasteries in Croatia were sent to prepare the liturgical books to be used in the abbey. One of the scribes was a monk named John. He and other Croatian monks who came to Prague became known among the Czechs as “pisarzi harvatsk” (Croatian scribes).

The pope Clement VI, who granted permission to the king Charles IV to use the Slavonic language in the sacred liturgy was a Benedictine himself. In the document the pope mentions the fact that many monasteries in Croatia celebrate the whole liturgy in the Slavonic language.

Conclusion

Benedictines in Croatia had a crucial influence on the development not only of the religious and cultural life of the Croatians but even on their political orientation as well. They brought and cultivated among them the Christian religion and Catholic institutions, schools, libraries, and all sorts of knowledge. They kept alive the Slavonic liturgical language until the Vatican II Church council in the 1960s. Up to that time, the use of the “native” language in Roman liturgy in Croatia was unique in the Catholic Church. That was an important element in preserving the Croatian national identity. Interestingly, the Croatian Benedictines were very staunch in guarding the Croatian native tradition, and, at the same time, they were a steadfast bridge between the church in Croatia and Rome.

Ante Čuvalo (May 1970)

Based on the following readings:

V. O. Kliuchevsky, A Cours in Russian History, The Seventeenth Century.

Paul Miliukov, Outlines of Russian Culture. Part I, Religion and the Church.

N. K. Gudzy, History of Early Russian Literature.

Serge Zenkovsky, ed. Medieval Russia’s Epics, Chronicles, and Tales.

Robert O. Crummey, The Old Believers and the World of Antichrist.

The Russian Church Council of 1666-7 excommunicated a large number of clergy and believers from the church. Those who found themselves outside the church became known as the Old Believers, because they did not want to accept a number of changes in the ritual and alterations in the liturgical books, which were ordered by the Council of 1654. Neither side wanted to compromise with the other. The official church considered the Old Believers as schismatic, while those that opposed the changes assumed that they were the holders of the true faith and it was the official church that broke away from the true Orthodoxy. Both sides condemned each other, and a permanent schism took place.

Officially, the main cause for the schism was the ritual change that was undertaken in order to bring the Russian liturgy and its books up to date with the Greek liturgical practices of the time. Those changes were not of a major nature. For example, the number of fingers to be used for crossing oneself is three instead of two; the number of alleluias and prostrations also was changed. Some expressions were to be changed in the liturgical books: ‘church’ for ‘temple’ and ‘temple’ for ‘church’; ‘infants’ for ‘children’ and ‘children’ for ‘infants’; and many other words or expressions of a similar nature. (Miliukov, p. 35) Patriarch Nikon also ordered all Russian-style icons to be destroyed. He himself participated in raids on icons in Moscow and in their destruction.

One of the fundamental causes for the split in the church was the traditional Russian belief that their church was the only true Christian church and the true guardian of the orthodoxy through which the salvation of the world would come—the so-called Third Rome doctrine. The leader of the Old Believers, the Archpriest Avvakum, expressed this belief clearly at the Council of 1666:

O you teachers of Christendom, Rome fell away long ago and lies prostrate, and the Poles fell in the like ruin with her, being to the end the enemies of the Christian. And among you Orthodoxy is of mongrel breed, and no wonder—if by the violence of the Turkish Mahmut you have become impotent, and henceforth it is you who should come to us to learn. By the gift of God among us there is autocracy; till the time of Nikon, the apostate, in our Russia under our pious princes and tsars the Orthodox Faith was pure and undefiled, and in the church there was no sedition. (Zenkovsky, p. 441)

To the logic of the Old Believers, the changes were undermining the foundations of the Russian Orthodoxy from two sides. On one hand, any change in ritual, books, icons, or anything else in the church practices had an implication that the past practices were not good, and the traditional Russian piety had not been truly orthodox. Even the lives of the Russian saints were in question. They became saints because of their faithfulness to the “old religion.” And now that “old religion” was in question and even condemned. On the other side, the issue was that the Russian church had to follow the Greek church in these ritual novelties, the church that had become “impure.” Constantinople, the second Rome, had fallen and its orthodoxy with it. And now, the Russian church was supposed to follow it.

To the Old Believers, this shift on the part of the Russian hierarchy meant the destruction of the third Rome doctrine and implied that the Russian church had deviated from the true Christian Orthodoxy. A clash had to come between the traditionalists and the modernists because the ritual changes touched the heart of the Russian tradition: piety and belief in its messianism.

The consequences of the fall of the third Rome were to be, in the eyes of the Old Believers, much greater than a split in the church. It meant that the end of the world was at hand. Moscow was the third and the final Rome. The changes in the Russian church were considered the work of the enemies of God, of the Antichrist’s emissaries, or of the Antichrist himself. There were various predictions about when the end of the world would come and who the Antichrist was. Even the year 1666 was taken as an apocalyptic symbol. Patriarch Nikon, Tsar Alexis, and most of all Peter the Great, later on, were considered as Antichrists.

Evidently, the third Rome doctrine was the heart of the problem in the schism controversy. The other reasons were secondary or, in some cases, related to it. This is clear from the writings of Avvakum. In his writings he did not dwell much on the ritual or the liturgical books. He preached against the changes because they were an expression of an evil undercurrent that was taking place in the Russian church. At the Council of 1666-7, he did not talk about the ritual but about the purity of faith: “…it is you who should come to us to learn.” In his autobiography he made an effort to prove that he and his followers were the holders of the true faith and that he was an instrument of God’s mission. He wrote to Alexis: “You reign supreme over the land of Rus alone, but to me the Son of God made subject during my imprisonment both sky and earth.” (Gudzy, p. 386) He imagined that he and his followers were now the only true Christians and the true witnesses of faith until Christ comes again. Considering the above-mentioned points, the authors did not treat the third Rome issue for Avvakum and his followers in depth as they should have.

A number of other reasons for the church split have been given by different authors. Zenkovsky, for example, in his introduction to The Life of Archpriest Avvakum by Himself, stresses the question of authority. When Nikon became Patriarch in 1652, he turned against those priests who tried to revive the Russian religious life (Bogoliubtsy), even though he used to be one of them. In their activities he saw “a threat to the authority of the hierarchy.” “Nikon sought the unquestionable submission of the Church to the authority of the patriarch. … Avvakum and his followers, who represented the lower clergy and their parishioners, felt that the parish priests and local laity should have a greater voice in Church affairs.” (Zenkovsky, p. 400)

Kliuchevsky also points out, “The question of ritual was replaced by that of obedience to ecclesiastical authorities. It was on this account that the council of 1666-7 excommunicated the Old Believers.” (p. 329) Crummey mentions in support of this argument that “the council of 1666 decreed that steps should be taken to curtail the autonomy of local communities in ecclesiastical affairs.” (p. 16) Certainly, the submission to the authority was an important question. But to Nikon and the official church it was obedience that mattered, while to Avvakum and the Old Believers it was a problem of conscience and faith. The problem of local autonomy, or the rights of the parishioners, it can be argued, was of secondary, lesser significance than Zenkovsky’s interpretation of events.

The foreign ideas that were influencing Russian cultural life, especially some members of higher political and social circles, were also contributing to the problems in the church. The novel ideas were coming from the West, from Kiev and Greece. In 1632 a monk called Joseph was sent by the patriarch of Alexandria to Moscow to translate Greek polemical books against Latin heresies into Slavonic. (Kliuchevsky, p. 297) Government itself supported learning and literary activities. In 1649 three learned monks from Kiev Academy were commissioned to translate the Bible from Greek into Slavonic. (Kliuchevsky, p. 295) Alexis himself was promoting learning, and he sent his sons to study under a monk who studied in Kiev. He had them learn Latin and Polish. (Kliuchevsky, p. 299) Some of the high court officials were men of knowledge and “westernizers.” One of the best-known promoters of learning at the time was Feodor Mikhailovich Rtischev, who was a trusted advisor of the tsar. He established a monastery near Moscow in 1649 and “installed there at his own expense as many as thirty learned monks from the Pechersky Monastery in Kiev and other Ukrainian monasteries, who were to translate foreign books into Russian and to teach Greek, Latin, and Slavonic grammar, rhetoric, philosophy, and other literary subjects.” (Kliuchevsky, p. 298) These are just some of the cultural activities, and they indicate a strong interest in learning and in Western ideas.